Seahorse

Seahorse

Acrylic ink, watercolours and fineliner pens on paper, 38×27 cm

I’ve only seen a seahorse once in my life when I was snorkelling. My sister saw him first, and

called my attention to him. It was tiny and colourful and left a long-lasting impression of

grace and mystery on me.

Seahorses live in seagrass beds and mangroves, that are important for climate change

regulation, and in coral reefs, that are severely affected by climate change.

Did you know that male seahorses carry the eggs of their progeny throughout gestation,

instead of female seahorses?

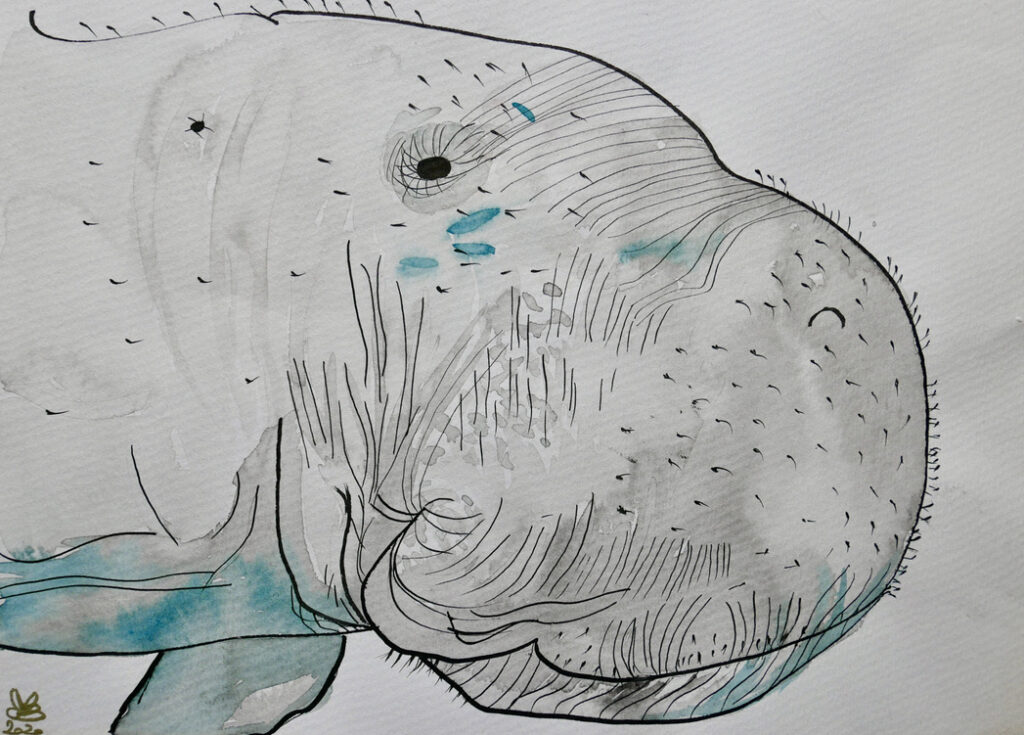

Manatee

Acrylic ink, watercolours and fineliner pens on paper, 38×27 cm

I’ve never seen a manatee in the wild, but have always been fascinated by their massive grace

in pictures and videos. It is no wonder they were considered mermaids in some knowledge

systems. Manatees are mammals and vegetarian. They are nicknamed ‘sea cows’ for their gentle

moving. They live in shallow coastal areas and rivers.

Did you know that manatees use their flippers to ‘walk’ along the bottom, dig for plants and

then scoop them up to their lips, so that they can eat them?

Ultra-black deep-sea fish

Acrylic ink, watercolours and fineliner pens on paper, 38×27 cm

Deep-sea fish are incredible beings that are able to live in the most inhospitable conditions –

without light, little food, cold temperatures and extreme pressures. A variety of deep-sea

fishes have ultra-black skin to be ‘invisible’ from predators and approach, undetected, their

own prey.

We still know little about the deep seas and the forms of life that inhabit them. In fact, did

you know that the moon is better mapped than the deep seas?

I have learnt a lot from deep-sea biologists and ecologists that contribute to the One Ocean

Hub – they may well be the true explorers on this planet, every deep-sea research trip

is a journey into the unknown and you can never anticipate what you will discover. That is why

it is so important that scientists from all over the world can participate in these scientific

expeditions, to contribute to understand the secrets of life on our planet together, instead of having only the scientists from the ten countries in the world that can afford the few multi-

million research vessels that are equipped for deep-sea exploration.

Manta ray

Acrylic ink, watercolours and fineliner pens on paper, 38×27 cm

I have never had a chance to see mantas in the wild, so it is one of my dreams. I have always

been fascinating by these ocean ‘birds’ that swim with wings. Mantas have the largest brains of all fish. They are filter-feeders, which helps to improve water quality.

Did you know that mantas may ‘breach’ (leap out of the water) and literally jump into air?

Dolphin

Acrylic ink, watercolours and fineliner pens on paper, 38×27 cm

The very first time I saw dolphins I was on an eco-volunteering trip with my sister, learning

from marine biologists and contributing to their efforts of monitoring dolphins in the wild in

Italian waters. For the first couple of days, we could not see any: we kept mistaking the shade

of waves for dolphin dorsal fins. But when we actually saw a dolphin, we realized that you

can’t mistake that for anything else. Since then, I have seen dolphins in the wild – from a

cliff, from a boat, and in the water while snorkelling and swimming next to them. The most

memorable experience has been when I went on an early-morning dolphin-watching trip with

One Ocean Hub researchers in Port Elizabeth, South Africa… after a while, we found

ourselves in a “river” of thousands of dolphins swimming along our boat. For a few,

exhilarating minutes, we were surrounded by their shimmering bodies appearing and

disappearing in the waves and nothing else mattered.

Dolphins are marine mammals that teach, learn and cooperate. They communicate with one

another with clicks and whistles. This is why they can be severely affected by noise pollution

in the ocean. See how One Ocean Hub researchers, small-scale fishers and other supporting

organizations have opposed the use of seismic surveys for offshore oil and gas exploration in

South Africa to prevent noise pollution, among other environmental and human rights threats:

see here and here.

Did you know that dolphins sleep with only one eye (and half of their brain) so that they can

keep swimming and breathing with the other?

Dugong

Acrylic ink, watercolours and fineliner pens on paper, 38×27 cm

Dugongs are marine mammals that live in seagrass. They are ‘cousins’ to manatees, but have

a dolphin-like tail instead of a large flipper. In the Solomon Islands, eating a dugong is forbidden, because according to a legend, a woman jumped into the sea and changed into a dugong. Traditional tales and customary rules of different communities are recognized internationally as important for both cultural diversity and environmental protection.

Did you know that there is a 5,000-year-old wall painting of a dugong in a cave in Malaysia?

On the importance of art and cultural heritage for ocean science and for ocean governance,

including human rights.

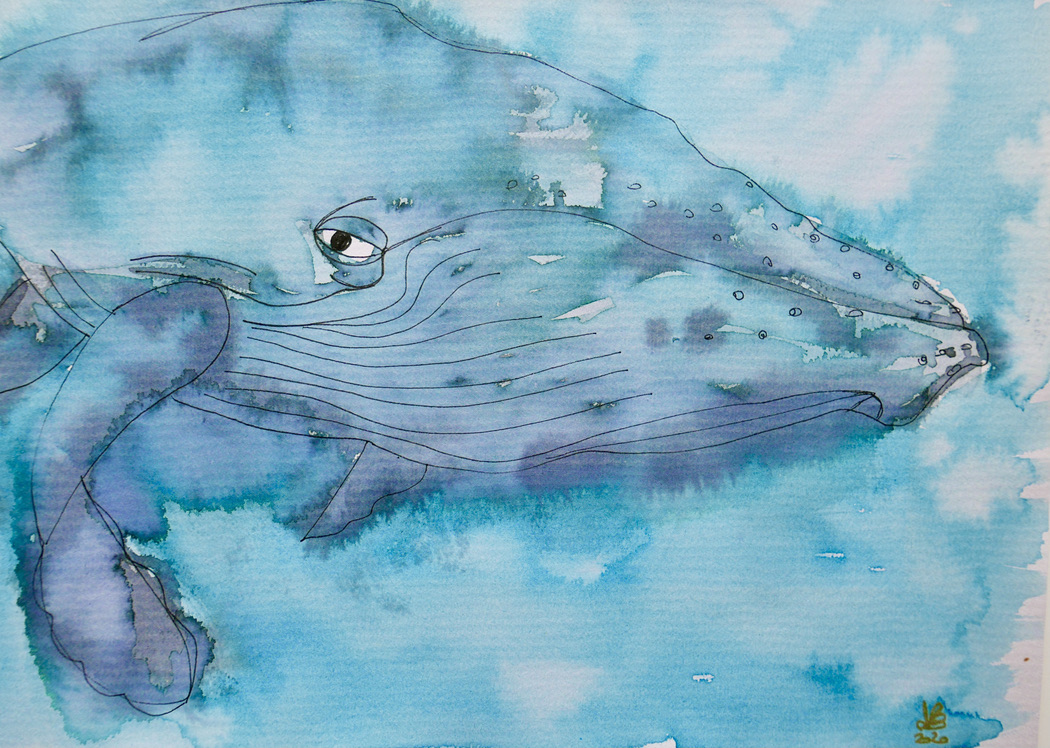

Whale

Whale

Acrylic ink, watercolours and fineliner pens on paper, 38×27 cm

I once ‘swam’ with a whale. I was snorkelling and she swam below me. It felt like both

the fastest and slowest experience of my life: the whale must have been quite far from me,

but because she is so large, she still felt quite close to me. I am still not sure if I really saw

her eye, while she passed me by.

The first essay I ever read was Among Whales by Roger Payne and the most fascinating thing

I learnt is that whales communicate with one another through songs. These songs are altered

when they are sung by different ways, so that they can contain new information. They can be

so elaborate that they have been compared to human epic songs.

Did you know that whales are conscious breathers? They cannot afford to become

unconscious when they sleep for long because they need to keep thinking about breathing.

Hammerhead sharks

Acrylic ink, watercolours and fineliner pens on paper, 38×27 cm

The hammer-like shape of the head of this shark helps them with their vision and perception

of depth. Hammerhead sharks have cultural significance for different indigenous peoples and for local knowledge. Overfishing is putting these and other sharks at risk of extinction.

Did you know that hammerhead sharks swim in schools of up to 50 members during the day,

but hunt alone at night?

About the artist

Elisa Morgera is an emerging, self-taught artist who draws (mainly with fineliner pens, soft pastels and water-soluble graphite), paints (mainly in ink and watercolours) and takes photographs. She is exploring visual arts as a way to learn to see differently and express more than she does through words, which she has privileged in her work as an international environmental law scholar and practitioner. Elisa is the Director of the One Ocean Hub and is Professor of Global Environmental Law and the University of Strathclyde, in Glasgow, Scotland. She is grateful to Dylan McGarry and Kira Erwin, co-researchers and practicing artists in South Africa, and to her sister Francesca, also a visual artist, for their encouragement and inspiration. Elisa also contributed to the One Ocean Hub’s Fishers Tales story-telling project.